- Original Article

- Open access

- Published:

Experiences of evidence presentation in court: an insight into the practice of crime scene examiners in England, Wales and Australia

Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences volume 10, Article number: 8 (2020)

Abstract

Background

The ability to present complex forensic evidence in a courtroom in a manner that is fully comprehensible to all stakeholders remains problematic. Individual subjective interpretations may impede a collective and correct understanding of the complex environments and the evidence therein presented to them. This is not fully facilitated or assisted in any way with current non-technological evidence presentation methods such as poor resolution black and white photocopies or unidimensional photographs of complex 3D environments. Given the wide availability of relatively cheap technology, such as tablets, smartphones and laptops, there is evidence to suggest that individuals are already used to receiving visually complex information in relatively short periods of time such as is available in a court hearing. courtrooms could learn from this more generic widespread use of technology and have demonstrated their ability to do so in part by their adoption of the use of tablets for Magistrates. The aim of this current study was to identify the types of digital technology being used in courts and to obtain data from police personnel presenting digital evidence in court.

Results

A questionnaire study was conducted in this research to explore current technology used within courtrooms from the perspective of crime scene personnel involved in the presentation of complex crime scene evidence. The study demonstrated that whilst many of the participants currently utilize high-end technological solutions to document their crime scenes, such as 360° photography or laser scanning technologies, their ability to present such evidence was hindered or prevented. This was most likely due to either a lack of existing technology installed in the court, or due to a lack of interoperability between new and existing technology.

Conclusion

This study has contributed to this academic field by publishing real life experiences of crime scene examiner’s, who have used advanced technology to record and evaluate crime scenes but are limited in their scope for sharing this information with the court due to technological insufficiency. Contemporary recording techniques have provided the opportunity for further review of crime scenes, which is considered to be a valuable property over previous documentation practice, which relied upon the competency of the investigator to comprehensively capture the scene, often in a single opportunity.

Introduction

The delivery of evidence in the UK Courts of Law in part involves extensive oral descriptions of events and evidence from an investigation, which can be a time consuming and laborious task (Schofield 2016). In terms of evidence relating to a crime scene, verbal statements, printed photographs and sketches of the scene may be used (Lederer 1994; McCracken 1999).

Conveying evidence from a scene, which both experts and laypersons can fully understand, remains an “ever-difficult task” (Chan 2005). This is because individuals may misinterpret or find difficulty in understanding the information being described to them (Schofield and Fowle 2013). It is entirely likely that cognitive processes contribute to variance in the interpretation of the evidence amongst listeners, and perhaps unsurprisingly, a survey conducted by the American Bar Association (2013) has demonstrated that significant volumes of technical information or complex facts can not only overwhelm the jury, but also often confuses them, leaving them feeling bored and frustrated (Kuehn 1999; Schofield 2009). In turn, this can present difficulties in absorbing and retaining information (Krieger 1992). Lederer and Solomon (1997) noted an increase in people’s attention when moving object displays were used in the courtroom.

There have been research studies which have investigated and considered the effects and impact that evidence presentation methods may have on jurors’ decisions in the courtroom (Schofield 2016; Schofield and Fowle 2013; Dahir 2011; Kassin and Dunn 1997; Dunn et al. 2006; Schofield 2011). Alternative research has started to develop our understanding of the effects that technology may have on jurors and the decisions which they make in the courtroom (Burton et al. 2005). Whilst visual presentation methods offer significant advantages in presenting complex evidence in an understandable way, research would suggest that such methods could also mislead, or unfairly persuade a jury (Schofield 2016; Burton et al. 2005).

Manlowe (2005) details the practical considerations which need to be made before introducing visual presentations into the courtroom, such as whether the technology installed permits graphical displays to be presented. Manlowe (2005) advocates the use of visual evidence in the courtroom in combination with oral presentations, as it has been found that jurors can retain six times as much information when compared with just oral presentations alone. Schofield and Fowle (2013) also extensively described the advantages and disadvantages associated with different graphical technologies for presenting evidence in the courtroom, and provided guidelines for using such evidence.

Given the availability of technical devices, such as tablets, smartphones and laptops, there is some evidence to suggest that individuals are used to receiving high-impact information in relatively short periods of time (Manlowe 2005; Pointe 2002). This information is highly visual, and as it utilizes technology might suggest that members of the court, including the jury, are equipped for a shift towards an increase in the quantity of visual data and technological advancement. It might also suggest that traditional methods of presenting evidence relating to a crime scene, such as sketches and photographs lack the flexibility and ability to deliver the intended information in a comprehensive manner. According to Manlowe (2005), basic demonstrative exhibits in the courtroom were time consuming and expensive and were limited in their ability to be edited. Technological advancements in the presentation of crime scene evidence include scene recording and visualization (Schofield 2016). Such technology ultimately aims to facilitate effective and rapid communication of crime scene environments between users within law enforcement agencies and in court (O’Brien and Marakas 2010; Manker 2015).

The presentation of forensic evidence using reconstructed virtual environments, such as computer-generated (CG) displays and virtual reality (VR) have been developed through the necessity to improve jurors’ understanding of complex evidence without technical, jargon-filled explanations. It is thought that jurors place more credibility on what they can “see and touch” (Schofield 2009). Virtual environments present unique opportunities to visually illustrate a scene, with the ability to “walk through” and virtually interact with the environment, and this can be more compelling for juries (Agosto et al. 2008; Mullins 2016). Howard et al. (2000) explored the use of virtual reality to create 3D reconstructions of crime scenes and demonstrated that the system they introduced made the evidence being presented to them easier to comprehend, and substantially shortened the length of trials.

Panoramic photography is another means of technological advancement that has been used to aid the presentation of crime scene evidence. In 2014, a 360° panorama was used to demonstrate material as part of a murder trial. The jury in Birmingham experienced a virtual “walk through” of a scene for a murder trial, created using an iSTAR® panoramic camera (NCTech). Warwickshire Police have used an iSTAR® camera to document serious road traffic collisions (RTCs), which contributed to the evidence revealed during the trial of Scott Melville for the murder of Sydney Pavier. Principal Crown advocate of the Crown Prosecution Service, Peter Grieves Smith commended the technology used stating “It was invaluable footage that greatly assisted the jury in understanding the layout of the property. It will surely become the norm to use this in the future in the prosecution of complex and grave crime”. Judge Burbidge QC also commended Warwickshire Police for their professional pursuit of justice in this case.

Reportedly, the state of courtroom technology integration differs significantly around the world (Manker 2015; Reiling 2010; Ministry of Justice 2013). Basic technology, such as tablets and television screens are being used within some courtrooms in the USA and Australia (Schofield 2011) with a limited number integrating more high-end technological solutions, such as CG presentations in the USA (Chan 2005). The integration of technology within the UK courtrooms is still in its infancy and is a significantly slower process than the USA or Australia (Schofield 2016). As part of a strategic new plan introduced in 2014, the UK criminal justice system was due to be transformed through digital technology. The plan sought to make courtrooms “digital by default” with an end to the reliance on paper by 2016, and to provide “swifter justice” through the digital dissemination of information (Ministry of Justice 2013). The ultimate aim was to digitize the entire UK criminal justice system by 2020, to simplify processes and improve efficiency. In 2013, Birmingham’s Magistrates court produced the UK’s first digital concept court, a courtroom that trialled technology to aid in the speed and efficiency of trials using laptops to store electronic case files as opposed to large paper folders, and to facilitate the sharing of files with other members of the courtroom.

In 2016, the UK National Audit Office conducted an investigation to determine the current situation of courtrooms in terms of the digital reform. Results demonstrated how some parts of the criminal justice system were still heavily paper based, creating inefficiencies. The report concluded that the time frames that were originally employed, were overambitious (National Audit Office 2016).

The aim of this study was to explore the current situation regarding technology use in courtrooms from the perspective of persons involved in the presentation of crime scene evidence, and to explore barriers and facilitators to its greater and effective use. In this study, the following objectives were considered: to establish the state of current literature associated with the use of technology in courtrooms; to obtain data regarding the experiences of the UK police service personnel with respect to presenting digital evidence in courtrooms; to identify the types of technology that are currently being utilized in courtrooms in the UK; to seek the opinions of police service personnel with regard to digital technology use in the courtrooms and to use these outcomes to define a fresh starting point to debate the exploitation of digital technology use in the UK courtrooms to facilitate more efficient, better value for money and robust judgements with complex forensic content.

The study has focused on the experiences of crime scene personnel because of the advancements of technology in this particular area, such as the use of 360° photography and laser scanning. The subject area also falls within the remit of the research team. By sharing opinions and experience, the paper hopes to aid both legal professionals and police service personnel to a more comprehensive understanding of the current use of technology in the courtroom, the advantages which technology can provide to their case, and the barriers which have been affecting the adoption of technology.

Methods

Participant questionnaires

A qualitative phenomenological research study was conducted to explore the experiences of police service personnel regarding the current use of information technology in courtrooms and in their experience of evidence presentation. The sample group included vehicle collision investigators and forensic photographers/imaging technicians. A snowball sample of 21 police service personnel from England and Wales and Australia were recruited via email and a UK police forum for participation within this study. It was considered useful to recruit participants from these countries because of the similarities with their respective criminal justice systems (McDougall 2016) but where differences in the rate of technology integration had also been previously reported (Schofield 2016) which could offer meaningful and experience based solutions in technological advancement.

Participants were required to formally consent to participation in line with the ethical requirements of the host institution. Participants were emailed a semi-structured, open-ended questionnaire and were asked to type or handwrite their responses. The questions asked were as follows:

- 1.

What is your job title and role within the criminal justice system?

- 2.

As part of your role, are you required to present evidence in a courtroom?

- 3.

Can you tell me what, if any, technology has been integrated into the courtroom?

- 4.

What has your experience been in terms of the introduction of new technology into the courtroom?

- 5.

Have there been any difficulties with technology being integrated into the courtroom?

- a)

With the implementation of technology with existing and current courtroom systems?

- b)

And whether there have been barriers, if any, to the adoption of such technology?

- c)

If there has not, why do you think this is?

- a)

- 6.

In terms of the current methods with which forensic evidence is presented in court, do you think anything needs to be changed? Please explain.

- 7.

What has your experience been with the presentation of evidence in court? Please explain.

- 8.

New technology is becoming available to police services and forensic services for the documentation and presentation of crime scenes. 360° photography or laser scanning is being implemented into police services to speed up the data capture as well as to capture more detail and information from the scene.

- a)

Have you had any experience in this area—do you yourself use these methods for documenting crime scenes?

- b)

Have you ever had to present this type of evidence in court? Please explain.

- a)

- 9.

What has the response been to this method of presenting evidence

- a)

From the judges?

- b)

Barristers?

- c)

The jury members?

- a)

- 10.

Is the courtroom fully equipped to allow you to present this type of evidence? Please explain.

- 11.

Do you feel there is anything, which needs improvement? Please explain.

- 12.

Can you give me your opinion on presenting evidence in this manner? Advantages/disadvantages.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis based on Manker (2015) methodology, originally adapted from Guest et al. (2012), was used to analyse the data that was collected from the 21 participants. The data analysis consisted of breaking down and coding the text responses obtained from the participants’ questionnaires, to identify themes and to construct thematic networks. A computer software program NVivo was used to store, organize and code the open-ended data collected from participants. Participant text responses were re-structured within an Excel spread sheet and the data set uploaded into the NVivo software. The data was explored using the NVivo software through word frequency queries to analyse the most frequently used words in the participant data. Emerging themes were identified and coded using specific keywords or “nodes”. Nodes were created based on these recurring themes, and any responses were coded at the relevant nodes. For example, for question 11 which asked the participants “What has the response been to this method of presenting evidence”, potential responses from participants could suggest a good response, a bad response, little response, no response or not applicable. These identified nodes would allow the researcher to link a node to the relevant response from participants. Within the NVivo software, the researcher could search nodes and easily identify all participants who had the same response. This was used to analyse the different themes identified within the participant data. As the analysis of the data progressed, new nodes were identified and these were checked against all other participants.

Thematic categories were determined by the researchers: to include courtroom technology, ease of use, implementation, limited use, recommendations, advantages and disadvantages. Some of the thematic categories were further broken down to include additional related categories. For example, courtroom technology was further broken down to include specific categories such as television screens, audio-visual technology, computers, 360° photography and laser scanning.

The nodes were associated with the thematic categories described above. The participant responses were analysed, described and tables created which documented the number of respondents to have reported such a response relevant to the nodes. The nodal frequency within each theme was used to determine the existence of trends within the data.

Results and discussion

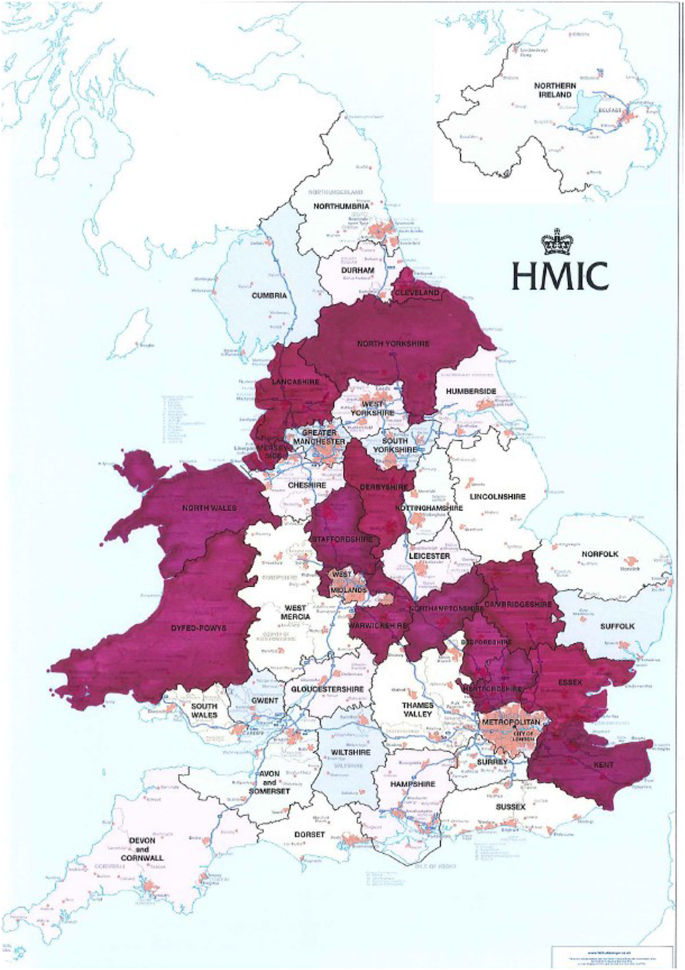

The purpose of this qualitative phenomenological research study was to explore and describe experiences of police service personnel with responsibilities within crime scene examination with regard to the current use of technology within the courtroom. This research covered over one third of the total 43 police services within England and Wales (15 services), as shown in Fig. 1. Each police service has their own policy and procedures for conducting criminal investigations and as such different individuals within the same police service would likely follow the same procedures.

Although the use of questionnaires allowed exploration of the participants’ experiences regarding the use of technology in the courtroom, they restricted further explanation or prompts for more detail which would be available in interviews. The authors accept that participant responses to questions that are likely to change based on different stimuli, such as the context of the request and their mood, in addition to what information they could recall from memory at that particular time. Consequently, participants may not recollect a particular experience or event at the time that they completed the questionnaire, and as a result may not mention it. In response to this, the paper presents a thematic analysis of the data, where collective themes are presented based on responses from the entire sample group rather than isolated incidents.

A consideration for the authors throughout the study related to the opportunities for participants to respond to questions in a manner that would be viewed favourably. This is termed “social desirability bias” (Manker 2015; Saris and Gallhofer 2014). As a result, participants may have been inclined to over exaggerate “good behaviour” or under report “bad behaviour”. Reportedly, the effects of social desirability bias is reduced in situations where an interviewer is not present, which is why, in part, the experimental design included questionnaire data. When the data was analysed, six themes were identified. These were “current technology in the courtroom”, “lack of technology in the courtroom”, “difficulties/barriers associated with the integration of technology into the courtroom”, “improvements/changes that are required”, “the future of courtroom technology” and “360° photography and laser scanning”.

Theme 1: Technology used in the courtroom

Within the first theme, participants were asked about their experiences of technology within the courtroom, which prompted responses that described the use of television screens, DVD players/CCTV viewing facilities, basic PC’s/laptops, paper files, photographs, basic audio-visual systems, live link capability, projectors and the specialist software to view 3D data. Four participants described how the current technology within the courtroom was limited to that of traditional paper files and printed albums of photographs. Given the use of the term “technology” within the question, the answers that were given were perceived to describe very basic methods, and some of the participants equally commented that “the courts need to catch up”. Those courtrooms that had initiated technology into trials had implemented what many participants claimed to be “basic and limited audio-visual technology”.

The UK National Audit Office (2016) identified that courtrooms have been slow to adopt technology and still heavily rely on paper files, which has worked for many years. The experiences described by the participants in this study would support these findings. The reason paper files have worked for many years could be attributed to the fact that people like to have something in their hands that they can see in front of them. Paper files and photographs allow a jury to look closely and examine what they are being shown, compared with distance viewing of a screen. However, printing photographs often leads to a loss in clarity and detail, which could make it more difficult to interpret what they are seeing. Often, it is the case that something may be visible on screen in a digital photograph that is not visible once recreated through print.

According to the data, the type of court and crime was a factor which determined whether any technology was implemented, and the type of technology that was implemented. For one participant, the majority of their cases were produced for the coroner’s courts, who were reportedly “yet to embrace” new evidential technology. It was also noted, however, that although slow to embrace technology, in the majority of cases at the coroner’s court, it was not needed.

Theme 2: Lack of technology in the courtroom

According to the results of this study, little technology had reportedly been implemented into the courtrooms. One participant stated that, “there has been little investment by the courts in modern technology” and “generally there hasn’t been any [implementation] and under investment seems to have been the greatest problem”.

Some of the participants described how limited technology had negatively impacted upon their ability to appropriately present evidence in court. In one instance the following scenario was described:

I was presenting evidence on blood spatter in court. The jury were looking at photocopies taken from the album of blood spatter on a door. So I had to ask the jury to accept that there were better quality images where the spatter could be seen and I was able to interpret the pattern. Not only does this allow a barrister to claim I was making it up but, it is much easier to explain something if people can see it.

A similar experience was reported by another participant, who took personal measures to aid their presentation of evidence:

I had to show each individual juror an original printed photograph from the report I had brought with me as those provided in their bundle were of such poor quality that the subject of my oral evidence was not clearly visible to them.

Primarily evidence is verbal, [and that the] presentation of photographs are by way of rather dodgy photocopied versions lovingly prepared by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

The significance of these statements relates to the potential for the evidence under presentation to be misunderstood or unfairly dismissed, which has implications for the case. These experiences would suggest that the most basic opportunities to provide equivalent quality photographs to the jury were missed. Forensic evidence is often highly visual, and even with an articulate speaker and extensive descriptive dialogue, the ability to effectively communicate the appearance and location of evidence such as blood spatter is likely to be strengthened by effective visual aids. Aside from high quality photographs, alternative digital presentation methods, such as portable screening devices may have provided an appropriate and just communication of the evidence.

Burton et al. (2005) and Schofield (2016) each made reference to the effects of visual presentation methods on jurors’ interpretation of evidence. In this research, reference has been made to actual evidence and not reconstructed scenarios; therefore, in our opinion, visual presentation opportunities to illustrate complex evidence such as blood spatter is only likely to improve jurors’ understating of the evidence being presented to them. It may also improve jurors’ retainment of information, as demonstrated by Manlowe (2005).

Paper files in the courtroom are still heavily relied upon, with the UK’s Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) producing roughly 160 million sheets of paper every year (Ministry of Justice 2013). In addition to the limited presentation quality of photocopied images, printed copies of two dimensional presentations were also criticized in terms of their inability to interact with jury members, as follows:

Tend to be clumsy and fill the witness box with paper that is pointed to in front of the witness and this is never conveyed to the jury.

If, maybe through the use of tablets, or some form of interactive media, this could be displayed on screen, then the witnesses’ thoughts and explanations may be better conveyed to the jury.

For other participants, the use of printed paper was seemingly appropriate:

For most cases, a simple 2D plan and photographs is more than sufficient. There is the ability to produce flashy reconstruction DVD’s, but I think there is a huge danger of a reconstruction showing things that did not happen, putting images to the court and jury that may only be a representation of a possible scenario rather than what is definite. This is particularly true for collision investigation where there are often unknowns and using a computer model cannot be certain that is what happened. Videos shown are talked through as they are run.

In this instance, the opposite explanation appears to be true. Here, the participant is suggesting that technology could facilitate the presentation of inappropriate and misrepresenting evidence, equally impacting negatively on the case. This would reasonably support the idea that the use of technology should be considered in the context of the evidence under presentation, and/or used in instances where facts are being communicated. The experiences described by this participant implied that the photographs that they had used had adequately supported the presentation of their evidence.

In cases where multiple types of evidence were being presented, the need for technology reportedly varied, but its availability was also restricted for some participants.

One participant described,

to date, I haven’t used any visual aids/props. Generally, I will have compiled a report, which contains photographs and a scale plan, but as part of the wider investigation there may be digital data such as CCTV footage, 3D laser scans and animated reconstructions. My evidence is given orally and the relevant sections of the jury bundle referred to for context. I have presented a case involving CCTV footage which was played on too small a screen for the jurors to see properly, therefore making it difficult for them to understand the intricacies of what it showed. The footage itself had to be provided in a format that could be played in a DVD player present in the courtroom, leading to an overall reduction in quality.

The restrictive nature of this environment for the presentation of CCTV evidence is surprising in a society that thrives on visual media. In this example, the presentation of evidence has been compromised for the cost of a larger screen, or the distribution of visual display devices, such as tablets. In terms of operation, these devices simply need to facilitate functions such as “play”, “stop” and “pause”. If there is a concern that jury members may be unable to comply, there are options to screen mirror devices, thus giving control to a single competent user. It was reported by an Australian participant that some courtrooms already had individual screens for each jury member. Many courtrooms in the USA had also installed multiple computer screens or individual tablets for the jury so that evidence was more easily viewed (Schofield 2016; Wiggins 2006).

One of the UK participants claimed that,

until the improvement of the visual aids for the jury i.e. much larger or closer/individual monitors are implemented even the products we provide at the moment are of limited use in the courtroom.

Any concern over difficulties with technology operation by jury members should be considered alongside the fact that according to the Office of Communications (Ofcom), in 2017, 76% of adults living in the UK had a smartphone; therefore, the authors question whether courtroom technological advancement should account for this and look at the cultural shift in technology. This was supported with the data, where a participant made reference to the introduction of technology into the courtroom stating how it can

depend very much on the attitudes of the judge, prosecutors and investigators. Some are technologically averse whilst others are happy to accommodate new technology.

In the USA, the courtroom 21 project (founded in 1993) has sought to address issues with technology integration into courtrooms by active research, demonstrating the software and hardware to users, as well as discussing ideas for use in court. This could be a useful learning opportunity for alternative justice systems moving forward, given that an evaluation of US courts in Rawson (2004) revealed some similarity between the US and UK current practice. There is some evidence to suggest that evidence presentation in the USA is similarly restricted by technological advancement.

The use of live links or videoconferencing, which allows expert witnesses to present their testimony off site was reported by two participants. This type of technology is widely used within courtrooms by police officers that can remain working until required to present evidence, to interview vulnerable witnesses, and to arrange suitable dates for a defendant’s trial. This is believed to save time and money transporting defendants to the courtroom location for hearings.

Theme 3: Difficulties/barriers associated with the integration of technology into the courtroom

This study highlighted some of the difficulties participants had experienced with the integration of technology into the courtroom and problems arising with the already installed basic courtroom equipment. One participant described,

people always seem to be finding their feet when trying to play with digital evidence, making things connect and work. Also, the actual devices are not always reliable

A lack of training and knowledge regarding existing technology was identified by several participants. One participant described the frustrations of the situations when technology was not operated correctly, describing,

the court clerk always seems to have difficulty getting the existing system to work correctly, albeit a DVD player. It is a great source of frustration for all involved.

And,

we occasionally use video footage, which has to be converted to DVD format to play at court –assuming the usher knows how to work it.

This raises a training issue within courtrooms, which was supported by the Rt Hon Sir Brian Leveson in his review of efficiency in criminal proceedings (Leveson 2015). In this document, the Rt Hon Sir Brian Leveson highlighted the requirement for judges, court staff and those individuals who have regular access to courtroom technology to be sufficiently trained. In addition, he highlighted the need for technical assistance to prevent underutilisation of technology due to technological failures, or defective equipment, which often delay proceedings (Leveson 2015). In 2014, 13 cases in Crown court and 275 in Magistrates were postponed because of problems with technology. The National Audit Office (2016) reported that the police had so little faith in the courts equipment that they hired their own at a cost of £500 a day.

Issues regarding the compatibility of technology in the courtroom and a lack of staff training are not restricted to the UK. A report generated by the Attorney General of New South Wales, Australia, identified the same issues arising from technology in the courtroom (Leveson 2015; NSW Attorney Generals Department 2013).

Participants’ reported lack of investment/funding as the most commonly occurring “barrier”. According to one participant,

Under investment seems to have been the greatest problem; we have the opportunity to bring 3D interactive virtual scenes to the courtroom for example, however the limited computing power available means that this is impossible and there is little or no will on the part of the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) to invest in this technology.

And,

CPS protocol is resistant to change and it also requires funding.

This supports the work of Manker (2015), who found that participants considered cost of equipment to be the main reason for the limited use of technology. Although technology may be expensive to purchase in the first instance, the significant returns should outweigh the initial expenditure. For example, technology aided trials may aid juries in understanding evidence, reaching a verdict and thus bringing the case to a close more quickly, reducing case costs and allowing more trials to be conducted concurrently (Marder 2001). In addition, there are benefits that cannot be quantified, such as juror satisfaction and engagement through the use of technology over laborious descriptions.

Barriers can also include a resistance to change or a lack of acceptance. One participant commented on the reluctance of individuals to accept new technology;

barriers include reluctance of some judges, investigators and lawyers to consider or implement newer technologies into their investigation or courtroom presentation … these challenges are reducing as time progresses and the technologies are increasingly established and the general paradigm is altered.

In some circumstances it may be necessary to integrate newer systems alongside, or in conjunction with, already existing equipment effectively. In many cases, the technologies may not be compatible, as evidenced through one participant’s response, who described,

the current systems seem incapable of keeping up with the advance on modern technologies or simply do not work more often than not.

Leveson (2015) found that many judges were in favour of exploiting technology in order to aid in the efficiency of the criminal justice system but had doubts regarding the ability to adapt current technology and its capacity to undertake its current duties.

This is not seemingly consistent with some participants’ experiences of technology outside of the courtroom, but within their investigative roles fear of technology and change also presents a barrier to the adoption of technology, particularly the risks associated with such technological change. Some changes may be successful, and others may not, but until these changes are made, it is impossible to know the outcomes of the technology use and what it can provide to the courtroom (Marder 2001).

There is some suggestion that technological change within courtrooms will be adopted. A report by the Ministry of Justice (2016) explains how the entire UK criminal justice system is being digitized to modernize courts using £700 million government funding. The funding aims to create a new online system that will link courts together. The digitisation of the UK criminal justice system is due to be completed in 2019, and an influx of funding should enable more rapid adoption of technology into the courtrooms.

Theme 4: Improvements/changes required to facilitate technological integration

Seven participants commented that no change in the courtroom was necessary with regards to technology. For example,

I think current methods are sufficient and like I said anything more complicated we provide our own laptop for.

As discussed, the technological requirements for evidence presentation are case specific, which is likely to be more prevalent in areas that utilize technology such as 360° photography and laser scanning.

Eight participants commented that a significant technological upgrade was required within courtrooms to cope with the ever-increasing demand of technology. This was emphasized in the following quotes:

The majority of courtrooms need a radical update. I’d hope that those being built now incorporate the required technology; however, I wouldn’t count on it,

the courts need full modernising,

the basic court infrastructure needs upgrading to allow it to handle the significant increase in demand that comes with the use of 3D animations software,

and,

the court process has changed very little in the 12 years I have been a collision investigator whilst the equipment we use and evidence we produce has changed exponentially.

The adoption of technology to aid with the documentation and recovery of evidence from crime scenes by police services can only support effective evidence presentation with the alignment of such technological advancements in the courtroom. Failure to align technology could mean that such evidence is unlikely to be presented in its most effective format. This change could be alleviated with the standardization of file formats. According to one participant,

standardisation of digital formats used in the courtrooms would help in the preparation of evidence knowing which format to use when supplying evidence, to police and the courts. The most common remark we get from police and the courts regarding digital file formats is “can you supply or convert this or these files to a usable format, we just need it to be playable in court”.

Theme 5: courtrooms of the future

Participants were asked about their thoughts on the future of evidence presentation. Virtual reality (VR) featured within several responses, with the idea being that courtroom users could be transported to a scene, allowing them to view and navigate themselves through it in 3D. Research has been conducted to investigate the use of VR courtrooms, whereby jurors wear VR headsets and are transported to the crime scene, allowing them to explore the scene (Bailenson et al. 2006; Schofield 2007).

In this study, one participant commented that,

When presenting evidence in an innovative way it generally means in a way that is better for the jury to understand, and that means clarity.

And,

This will provide the ability for jurors, judges and the coroner to revisit a scene without leaving the courtroom and see things from the perspective of various people involved (victim, accused, witnesses).

In terms of its overall aim, one participant commented,

The aim is surely to assist the jury with understanding the complexities of the crime scene and to do that they need to be able to visualise the location and the evidence identified within it so I believe the future of a courtroom will be to provide this as realistically as possible.

This participant does not state what technology will be used to provide this experience to the jury only that the visual evidence will need to be as realistic as possible.

The effectiveness of VR technology for evidence presentation is likely to encourage debate, given the clarity with which crime scenes can be presented, but with the consideration of contextual information and its effects on juror response.

There will however be a fine line between giving a jury enough information with which to make an informed decision and traumatising them in vivid technicolour. Technology should not be adopted for the sake of it as this could have profound effects on the trials outcome. Any evidence presented in a courtroom needs to describe the incident that occurred in a manner which is easily understandable.

Although the perceived benefits of the technology were discussed by some, other participants commented on how VR was “still a long way off from being used for evidence”. Issues regarding the persuasive impact of demonstrative evidence have already been explicitly expressed with regard to 360° photography and laser scanning (Narayanan and Hibbin 2001). Other researchers claim that such evidence can lead a jury to blindly believe and accept the evidence, as shown in the work of Schofield and Fowle (2013) and Selbak (1994). Consequently, the use of visual presentation using CG could have profound implications on the case outcome if the jurors instantly believe what they are seeing. Evidence presented in such a way must remain scientifically accurate and truthfully reflect the scientific data and augment witness testimony (Manker 2015). This was supported by participant comments regarding the probative value of the evidence. Here,

the probity value is yet to be determined, in addition to juries not being allowed on many occasions to witness certain graphic images for fear of being overly influenced. Virtual reality would compound this.

Another participant commented that,

it may be perceived as entertainment rather than a judicial process.

Theme 6: 360° photography and laser scanning

Given the considerable amount of technology available with respect to crime scene documentation, such as 360° photography and laser scanning, and the expertise of the participant group, participants were asked to describe their experiences of such technological advancements.

Most participants (18 out of 21) described how their respective police services currently utilize 360° photography or laser scanning methods to document their crime scenes, but due to limitation of the court, facilities were unable to present such evidence to the courts. In such situations, 3D laser scan data was used to create 2D plans which were then printed for the court. This was criticized by one participant, who expressed their opinion on having to print 2D plans as,

a travesty really when you consider what capability this data offers.

Often, such technology requires access to a data cloud, which raised an issue for two participants for evidence presentation.

One participant stated that it is,

unfortunate as the benefits of the data cloud as a contextual visual aid are unrivalled. In situations where the 3D data was allowed, it was only accepted into the court as a 3D animated “fly-through” played directly from a DVD. This participant stated that using this DVD method it was not possible to move through the scene in real time.

One participant did report being able to successfully present their 360° panoramas.

I was the first to show 360° panoramas along with point cloud data. I had to explain to the court what it was and how it was used prior to the case commencing. We have presented this type of evidence now in live court 3 times and received no criticism. There have been at least another 3 cases where we have produced it but not required to show it. It does require some advanced preparation and several visits to the court room to be used, to make sure it all works.

Conclusion

This study has contributed to this academic field by publishing real life experiences of crime scene examiner’s, who have used advanced technology to record and evaluate crime scenes but are limited in their scope for sharing this information with the court due to technological insufficiency. Contemporary recording techniques have provided the opportunity for further review of crime scenes, which is considered to be a valuable property over previous documentation practice, which relied upon the competency of the investigator to comprehensively capture the scene, often in a single opportunity.

With the Ministry of Justice driving the adoption of technology and providing significant funding to ensure the uptake of technology by courtrooms, it is inevitable that courtrooms will become “digital by default”. This will provide a more efficient CJS and allow information transfer to become more seamless.

The results of the qualitative phenomenological research in this study identified six key themes from the responses of participants, representing 15 of the current 43 UK police services. The themes covered the “current use of technology in the courtroom”, “lack of technology in the courtroom”, “difficulties/barriers associated with the integration of technology into the courtroom”, “improvements/changes that are required for technology integration”, “the future of courtroom digital technology”, and “360° photography and laser scanning”. The participants reported a general lack of technological integration within any court environments. It was clear that a significant change is required to existing courtrooms and their infrastructure to allow the use of existing technology to be utilized effectively, particularly for crime scene documentation, such as 360° photography or laser scanning from crime scenes or of evidence types. These areas, along with virtual reality represented aspects which participants believed would describe future-proofed courtrooms. However, concerns were voiced by the study group questioned, over the contextual influence that immersive technology may potentially cause and questioned the need to expose jurors to such information. Clearly, not only does digital-technological development within the courtroom require consideration, the attendant psychological benefits and ethical aspects also require developing in parallel to make the use of digital technology a fully useful and integrated feature in the decision-making process of Jurys and the UK courts and to provide a digital end-to-end common platform. As part of the ethical concerns to be addressed and those of “evidence continuity and potential contamination” of data, the opportunity that may exist to manipulate visual images needs to be carefully explored and future-proofed into any systems being developed. The authors firmly believe and attest that there is considerable scope for exploring this area further, although realize that the restricted access for courtroom presentation are likely, which limits the academic study of this area.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CG:

-

Computer generated

- CJS:

-

Criminal justice system

- CPS:

-

Crown Prosecution Service

- VR:

-

Virtual reality

References

Agosto E, Ajmar A, Boccardo P, Tonolo FG, Lingua A (2008) Crime scene reconstruction using a fully geomatic approach. Sensors 8:6280–6302

American Bar Association (2013) In: Poje J (ed) ABA Legal technology survey report. Volume VI. Mobile Lawyers

Bailenson JN, Blasovich J, Beall AC, Noveck B (2006) Courtroom applications of virtual environments, immersive virtual environments and collaborative virtual environments. Law Policy 28(2):249–270

Burton A, Schofield D, Goodwin L (2005) Gates of global perception: forensic graphics for evidence presentation. In: Proceedings of ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, ACM Press, Singapore, pp 103–111

Chan A (2005) The use of low cost virtual reality and digital technology to aid forensic scene interpretation and recording. Cranfield University PhD Thesis, Cranfield

Dahir VB (2011) Chapter 3: digital visual evidence. 77-112. In: Henderson C, Epstein EJ (eds) The future of evidence: how science and technology will change the practice of law. American Bar association, Chicago

Dunn MA, Salovey P, Feigenson N (2006) The jury persuaded (and not): computer animation in the courtroom. Law Policy 28(2):228–248

Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E (2012) Applied thematic analysis. Sage, Thousand

Howard TLJ, Murta AD, Gibson S (2000) Virtual environments for scene of crime reconstruction and analysis. In: Proceedings of SPIE - International Society for Optical Engineering, p 3960

Kassin S, Dunn MA (1997) Computer-animated displays and the jury: facilitative and prejudicial effects. Law Hum Behav 21(3):269–281

Krieger R (1992) Sophisticated computer graphics come of age—and evidence will never be the same. J Am Bar Assoc:93–95

Kuehn PF (1999) Maximizing your persuasiveness: effective computer generated exhibits. DCBA Brief J DuPage County Bar Assoc, 12:1999-2000

Lederer FI (1994) Technology comes to the courtroom, and.... . Faculty Publications. Emory Law J 43:1095–1122

Lederer FI, Solomon SH (1997) Courtroom technology – an introduction to the onrushing future. In: Faculty Publications. 1653. Conference Proceedings. Part of the Fifth National Court Technology Conference in Detroit, Michigan

Leveson B (2015) Review of efficiency in criminal proceedings by the Rt Hon Sir Brian Leveson. President of the Queen’s Bench Division. Judiciary of England and Wales

Manker C (2015) Factors contributing to the limited use of information technology in state courtrooms. Thesis. Walden University Scholarworks, p 1416

Manlowe B (2005) Speaker, “use of technology in the courtroom,”. IADC Trial Academy, Stanford University, Palo Alto

Marder NS (2001) Juries and technology: equipping jurors for the twenty-first century. Brook Law Rev 66(4). Article 9):1257–1299

McCracken K (1999) To-scale crime scene models: a great visual aid for the jury. J Forensic Identification 49:130–133

McDougall R (2016) Designing the courtroom of the future. Paper delivered at the international conference on court excellence. 27-29 January. , Singapore

Ministry of Justice. (2013) Press release - Damien Green: ‘digital courtrooms’ to be rolled out nationally. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/damian-green-digital-courtroomsto- be-rolled-out-nationally

Ministry of Justice (2016). Transforming our justice system. By the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice and the Senior President of Tribunals September 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/553261/joint-vision-statement.pdf

Mullins RA (2016) Virtual views: exploring the utility and impact of terrestrial laser scanners in forensics and law. University of Windsor. Electronic Theses and Dissertation Paper. University of Windsor, 5855

Narayanan A, Hibbin S (2001) Can animations be safely used in court? Artif Intell Law 9(4):271–294

National Audit Office (2016) A report by the Comptroller and Auditor General: Efficiency in the Criminal Justice System. Ministry of Justice Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2016/03/Efficiency-in-the-criminal-justice-system.pdf

NSW Attorney General’s Department (2013) Report of the Trial Efficiency Working Group. Crim Law Rev Division Available from: http://www.justice.nsw.gov.au/justicepolicy/Documents/tewg_reportmarch2009.pdf

O’Brien JA, Marakas GM (2010) Management information systems, 10th edn. McGraw-Hill, Boston

Pointe LM (2002) The Michigan cyber court: a bold experiment in the development of the first public virtual courthouse. North Carolina J Law Technol 4(1). Article 5):51–92

Rawson B (2004) The case for the technology-laden courtroom. Courtroom 21 project. Technology White Paper

Reiling D (2010) Technology for justice: how information technology can support judicial reform. Leiden University Press, Reiling, Leiden

Saris WE, Gallhofer IN (2014) Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research, Wiley series in Survey Methodology, 2nd edn. Wiley, New Jersey

Schofield D (2007) Using graphical technology to present evidence. In: Mason S (ed) Electronic Evidence: Disclosure, Discovery and Admissibility, vol 1, pp 101–121

Schofield D (2009) Animating evidence: computer game technology in the courtroom. J Inf Law Technol 1:1–21

Schofield D (2011) Playing with evidence: using video games in the courtroom. Entertainment Comput 2(1):47–58

Schofield D (2016) The use of computer generated imagery in legal proceedings. Digit Evid Electron Signature Law Rev 13:3–25

Schofield D, Fowle KG (2013) Technology corner visualising forensic data: evidence (part 1). J Digit Forensic Secur Law 8(1):73–90

Selbak J (1994) Digital Litigation: The Prejudicial Effects of Computer-Generated Animation in the Courtroom. High Technol Law J 9(2):337–367

Wiggins EC (2006) The courtroom of the future is here: introduction to emerging technologies in the legal system. Law Policy 28(2):182–191

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants who took part in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS collected, analysed and interpreted the participant data regarding the use of technology in the criminal justice system with assistance from SF and JP. All authors were contributors in writing the manuscript and reading and approving the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was considered using agreed university procedures and was approved by Staffordshire University.

Consent for publication

All data collected from the questionnaires was anonymised and it is not possible to identify the individuals who took part in the study through their statements or quotes. Participants were asked to sign a consent form stating that they understand that the data collected during the study would be anonymised prior to any publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheppard, K., Fieldhouse, S.J. & Cassella, J.P. Experiences of evidence presentation in court: an insight into the practice of crime scene examiners in England, Wales and Australia. Egypt J Forensic Sci 10, 8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-020-00184-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-020-00184-5